As educators, we are all interested in providing effective and engaging instruction for our students. Questions arise, however, on high leverage ways to accomplish this goal. Four new studies, funded by the Lucas Education Research Foundation, produced evidence that rigorous project-based learning improved outcomes for students across racial and socio-economic backgrounds. Key findings of four peer reviewed studies found the following:

- High school students who took AP courses with a focus in project-based learning (PBL) were likely to receive a credit-qualifying score of 3 or higher versus students that received traditional instruction.

- Researchers at the University of Michigan and Wisconsin found that third grade students completing PBL in science not only outperformed their control group peers, but also scored better in areas of collaboration and reflection, two important components of social and emotional learning.

- Another study from the University of Michigan investigated the effects of a PBL social studies curriculum on second graders in typically low performing schools. Students exposed to the curriculum gained about 6 months more growth in social studies and two months more growth in literacy compared to their peers in traditional non-PBL classrooms.

- Stanford University researchers tested PBL science curriculum, the Learning Through Science and Mathematics Project, on middle school sixth graders. The experimental group outperformed their controls by 11 percentage points on an NGSS assessment on the scientific practices.

The Difference Between Assigning a Project and Project-Based Learning

Most teachers are aware of, and probably have assigned projects at the end of a unit. As a former science teacher, and current science coach at Teaching Matters, educators and I have designed projects at the end of a unit in order to reinforce content. Some of our assigned science projects have asked students to:

- Choose a human body system, research the structure and function of the organs, and explain how the body system would work in conjunction with one other body system.

- Create a newspaper article (or short video) about an invasive species in students’ local communities.

- Make a comparison between a cell and its organelles, and a city and the structures within it.

- Build models comparing and contrasting plant and animal cells.

All of our projects had their merits. They were assigned to students for content review, to encourage research, digital literacy and presentation skills, and to offer an alternative (at times) to a paper and pencil exam. Sometimes, students were offered a choice of formats to experiment with in order to make the execution of the project more enjoyable – edible cell models fulfilled the “fun factor” well.

However, project-based learning (PBL) is a step above assigning a traditional project. Its core, “learning by doing” dates back to the 1600s, where project-based learning was meant to engage learners in solving meaningful and authentic problems that interested a learner. It has always involved an active approach, leading to a deeper understanding and engagement with content. Project Based Learning Works, an organization that supports teachers in utilizing PBL, makes the analogy between traditional projects and current project-based learning to “dessert” versus the “main course.” A typical end of unit project is a culminating activity after the unit content is already taught, whereas project-based learning is “the unit” in and of itself. It is the project that drives the unit, as opposed to a unit driving the project. Rigorous PBL requires critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration, and communication. It usually results in a publishable product at the end. Project-based learning units are good fits for encouraging student activism, environmental justice, civics, and social justice awareness, since they can be designed around particular issues that students themselves are faced with.

Examples of Project-Based Learning

In an elementary science curriculum, students in Michigan studied plant life cycles, while learning how to design gardens that could grow fresh food. An eighth-grade math and science teacher in San Francisco, Ms. Dominguez, knew her students cared about walking and bicycling safety in their city. Her curriculum included Newton’s Laws of Motion, (an object’s motion will not change unless an unbalanced force acts on it, the force on an object is equal to its mass multiplied by its acceleration, and for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction). These laws are foundational to the study of collisions. Eighth grade students used their knowledge from the unit to come up with ideas that could protect pedestrians and cyclists in San Francisco, such as the installation of speed bumps, and decreasing speed limits in certain areas.

Examples of other project ideas could be:

- How can we improve the quality of our school lunch?

- How can my family reduce its carbon footprint?

- How can a business reduce its waste?

- How can we design a city of the future that can withstand the effects of climate change?

- Interviewing older family members stories that contain words of wisdom we can all learn from

- How can we solve the problem of “fake news?”

My Experience with Project-Based Learning as a Science Coach

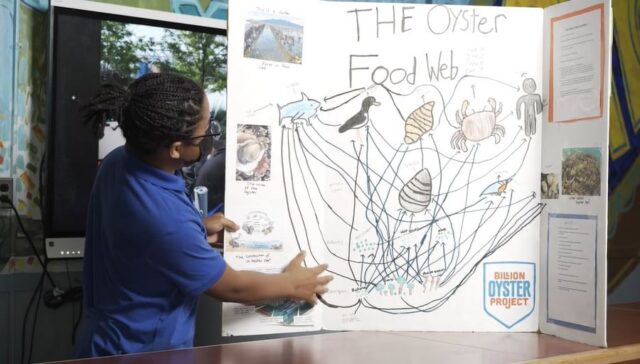

K050 is a middle school in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, serving primarily low-income students, and it is one of the schools in which I coach science. Its visionary principal, Ben Honoroff, developed a partnership with the Billion Oyster Project, BOP, a non-profit organization dedicated to restoring the NYC coastline with over a billion oysters. This partnership led to our small science department revamping its curriculum so that project-based learning about water quality in the vicinity of the school could take place.

Oysters are natural water filters, and until about the 1920s, NYC harbors were filled with oysters. Oysters were part of a complex ecosystem that included seals, birds (oystercatchers), mussels, fish, horseshoe crabs, sea gulls, and of course, humans. It is the hope of the BOP to restore the habitats of NYC waterways along with partnering with various NYC public schools. K050 is located about 4 blocks away from newly created Domino Park, which is used by Williamsburg community members and students alike. Cages with live oysters were installed at Domino. Principal Honoroff arranged student schedules so that classes could walk to the park, observe living animal and plant specimens, and measure oyster growth (and death).

Many students were engaged on the field trips. They were able to critically see (and touch) not just juvenile and adult oysters, but sea squirts, tunicates and their flowery orange patterns seen with hand lenses, very small mussels, sea anemones, and tube worms – in short – a whole new world of small invertebrates that our children had never observed before. Our middle schoolers may have lacked background knowledge, but showed extremely sharp observation skills. They found joy in showing us specimens that we “teachers” had overlooked. I had asked a few students what they had learned during the field trip. One student responded, “I learned that nature has many interesting patterns and is beautiful.” (This statement would warm any science teacher’s heart!) The BOP/K050 partnership was a perfect opportunity for our students to learn about environmental justice, how to improve water quality in their own communities, and how to encourage a future food supply for local businesses and future Williamsburg residents. Students completed their PBL projects at the end of the school that were publicly displayed at a symposium on Governor’s Island, giving them an opportunity to discuss their work with adults and students from other schools. Two groups even received awards for exemplary work.

Next year, one of Teaching Matters’ high schools will be partnering with BOP and both chemistry and earth science classes will be investigating water quality and landscape features in Soundview Channel, giving students ways to get to know and improve the communities they live in.

My Experience with the Challenging Aspects of Project-Based Learning

There is no question that project-based learning has a few challenges. It is hard work. It takes time to investigate issues that students might be interested in, and fore-thought in the things that can go wrong. Field trips to Domino Park in Williamsburg, Brooklyn required more work than we realized. Permission slips had to be obtained, and the metric system had to be taught to 6th graders so that they could measure oysters using calipers. More adult supervision was needed as we walked to the park in a given time frame. Oyster cages broke due to the force of the current, and their contents were lost. Buckets to collect water disappeared in the East River because we “forgot” to tie them to a solid land surface. Rainy forecasts could cancel trips. Oysters in classroom tanks died. All of us had a learning curve – and needed to learn about the life cycles of many species of organisms. Class management also became an issue at certain points in the unit. Students did not all finish projects at the same time. We had groups working on projects while others were doing math. Some students did not complete their projects due to a variety of circumstances, including difficulties with the English language.

The teachers and I had quite a few meetings debriefing about what went wrong and what could have been done to improve student experiences. Modifications were made. We chose student monitors and gave them their “jobs” ahead of time. Teachers and administrators tried to recruit parent volunteers. We used digital permission slips and re-taught the metric system. Scores of graphic organizers had to be created. Materials needed to be translated. Students had to be taught digital skills. We had to learn from our many mistakes.

After a lot of hard work, students experienced the joy of seeing dozens of new species, doing real hands-on science investigations, and the satisfaction of playing a role in the improvement of their own community. They also learned quite a bit of science. Many took quite a bit of pride in their work. I am proud of our students and the entire staff at K050. You might ask, “are we doing oyster projects again at K050 this year?” My answer is an equivocal “yes.”

Interested in working with educational consultants like Edith to bring effective project-based learning into your school? Contact us today to learn more about our coaching services.